My research and writing time, always too hard to come by, have taken me in various directions, but Tinsel is patiently waiting for me to do more than update the CV and instead to begin using it again as a record of my work, plans, inquiries. So here I am.

A piece long in the pipeline, “Gender Identity and Promiscuous  Identification: Reading (in) Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier,” has recently been published in The Journal of Modern Literature 40.3 (in the company of a “Woolf cluster!” Oh lucky day!). The paper has been described in this way:

Identification: Reading (in) Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier,” has recently been published in The Journal of Modern Literature 40.3 (in the company of a “Woolf cluster!” Oh lucky day!). The paper has been described in this way:

Jenny Baldry, the narrator of Rebecca West’s First World War novel _The Return of the Soldier_, has traditionally been discussed as a detached observer or unreliable raconteur of the narrative’s wartime love triangle. But she may be productively understood not only as one who tells the story, but as one who reads and interprets it. Positioned as reader, Jenny breaches appropriate boundaries between herself and the “characters” or primary participants in the events, exhibiting a radical empathy that Susan David Bernstein calls “promiscuous identification.” In doing so, she destabilizes not only her family and class loyalties but her very self. Jenny absorbs and appropriates others’ passions, and, even more strikingly, unsettles her gender identity through zealous identification with her male cousin Chris, even attempting to psychically access the masculine battlefield. Jenny’s desire, class allegiance, and gender identity, all complicated by her reading practice, challenge the novel’s stated moral and its seemingly inevitable conclusion.*

Additionally, the book From Page to Place: American Literary Tourism and the Afterlives of Authors (U Mass P, 2017, eds. Hilary Iris Lowe and Jennifer Harris) has recently come out and includes my chapter, “‘Afoot with my Vision’: Whitmania and Tourism in the Digital Age,” a piece that is meaningful to me in many ways, but not least because it grew out of a fantastic teaching experience, funded by the NEH as the multi-university project Looking for Whitman. The chapter is described in this way:

come out and includes my chapter, “‘Afoot with my Vision’: Whitmania and Tourism in the Digital Age,” a piece that is meaningful to me in many ways, but not least because it grew out of a fantastic teaching experience, funded by the NEH as the multi-university project Looking for Whitman. The chapter is described in this way:

This essay draws upon my experience as a teacher of a digitally-inflected seminar on the American poet Walt Whitman in examining how our practices and experiences as literary tourists are affected by the promises of accessibility and immediacy on the internet. The essay raises questions about what “seeing things” really means, questions that are entwined for me with Whitman’s own exhortations: “You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, [. . .] nor feed on the spectres of books,” he tells us, “You shall not look through my eyes either.” What is the difference between our eyes and the lens of the digitizing scanner or photographer? How do we “remember” something we see in person when the digital images of it that are available are all of higher quality but framed by someone else? When we tour online, are we taking things at second or third-hand? Or, instead, are we fooling ourselves that we are really, truly seeing through an author’s eyes and not just our own when we stand in the author’s prior physical spaces?**

My slow work on the poetess/periodicals and my somewhat-too-immersive work on literature of the Great War (and all things GW) have also inspired conference papers on H.D. and Charlotte Mew, at the unspeakably awesome conference H.D. and Feminist Poetics in Bethlehem PA, and on Mary Borden (new but relatively intense person of interest, sure to reappear) in a seminar on the First World War at MSA in 2015.

Phew.

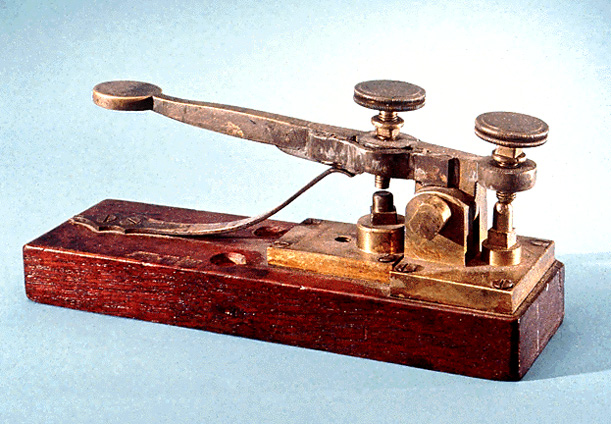

The poetess is again a little bit on hold as I am currently working on another article, the premise of which has been knocking around in my brain for awhile, which focuses on  H.D’s use of tropes and language of telegraphy and Morse code across several works. An earlier paper at SAMLA began this process, including some exploration of the artist-inventory Samuel Morse himself (an interesting but unpleasant fellow tbh) and starting to sketch out some ideas I have about the figure of the “active receiver” in H.D.’s aesthetic theory. So I’ve been reading a LOT about telegraphic history etc. and trying to grasp why a modernist writer, in an era literally defined by the rapid pace of its technological inventions, repeatedly turns on multiple occasions to a not-obsolete-but-decidely-19th-century-and-problematically-connected-to-news-of-tragedy-in-WWI technology. Gentle reader, to be continued….

H.D’s use of tropes and language of telegraphy and Morse code across several works. An earlier paper at SAMLA began this process, including some exploration of the artist-inventory Samuel Morse himself (an interesting but unpleasant fellow tbh) and starting to sketch out some ideas I have about the figure of the “active receiver” in H.D.’s aesthetic theory. So I’ve been reading a LOT about telegraphic history etc. and trying to grasp why a modernist writer, in an era literally defined by the rapid pace of its technological inventions, repeatedly turns on multiple occasions to a not-obsolete-but-decidely-19th-century-and-problematically-connected-to-news-of-tragedy-in-WWI technology. Gentle reader, to be continued….

… .. –. -. .. -. –. / — ..-. ..-.

* mns obsessions here noted: fluid gender identity; promiscuous identification and emotional contagion aka Why I Have a Long List of Books I Can Barely Think About Let Alone Teach Because They Make Me Too Emotional or Crazy; the Great War; madwomen; things the beautiful Rebecca West wears on her head especially beaded headdresses and sooomething on the cover of Time that could be an alien face or a coded yonic symbol.

self-evident

the beaded headdress

** mns obsessions here noted: the aged WW and his eyes; literary tourism and graveyards; my Whitmaniacs of 2009-10; the haversack; the Civil War in Virginia; the word “hirsute” but not hirsutism.

Even those with the funds to produce on thick paper or with stronger covers couldn’t have imagined that, a century later, the issues would be digitized

Even those with the funds to produce on thick paper or with stronger covers couldn’t have imagined that, a century later, the issues would be digitized